Building Inside Constraint

By InnerKwest Editorial Desk | February 19, 2026

InnerKwest Institutional Studies Series

Download the Full Reference Edition (PDF)

Includes expanded analysis, institutional diagrams, and contraction modeling.

Download the PDF →HERE

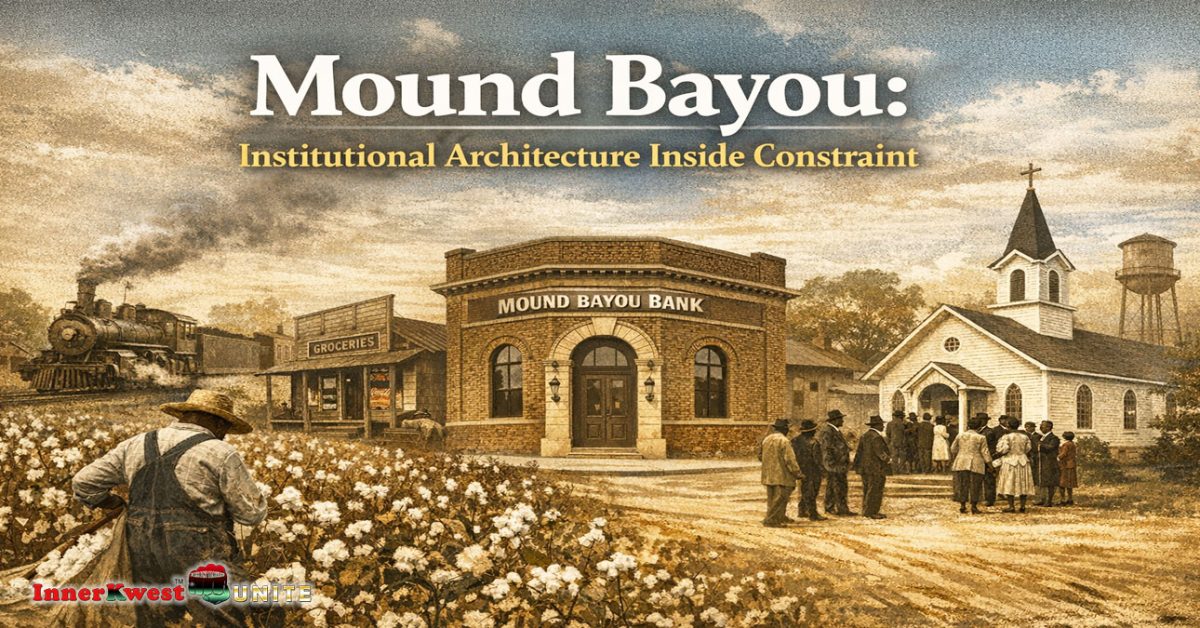

In 1887, when Mound Bayou was founded, the American South was not in a period of transition. It was in a period of consolidation.

Reconstruction had formally ended in 1877. Federal troops had withdrawn. Southern state governments moved quickly to restore political hierarchies that had briefly been disrupted. The language of constitutional revision was procedural. The intention was structural.

Mississippi led.

The Mississippi Constitution of 1890 introduced literacy requirements, poll taxes, and discretionary voter qualification clauses that effectively reshaped the electorate without naming race explicitly. Other Southern states soon followed: South Carolina in 1895, Louisiana in 1898, Alabama in 1901, Georgia in the early 20th century. The strategy was coordinated in outcome even if decentralized in drafting.

Political disenfranchisement did not operate alone. It was paired with economic architecture.

Across the Mississippi Delta and the broader Deep South, agricultural production rested on plantation systems and the crop-lien credit mechanism. Under this arrangement, farmers — many of them formerly enslaved or their descendants — borrowed against anticipated harvests. Supplies were extended on credit. Interest and markups were embedded in merchant pricing. Cotton revenue at harvest settled accounts, often incompletely. Debt rolled forward.

Debt in this system was not simply financial. It was positional.

It constrained mobility.

It constrained bargaining power.

It constrained land acquisition.

And because credit intermediaries were often aligned with plantation interests or white-controlled banking institutions, the cycle reinforced hierarchy.

Extralegal violence reinforced the system’s boundaries. Economic intimidation, forced evictions, and lynching were not merely expressions of racial hostility. They functioned as deterrence against upward mobility and political assertion. Across Mississippi, Louisiana, Alabama, and South Carolina, violence and law interacted as parallel enforcement systems.

Within this environment, autonomous institutional development was improbable.

Not impossible.

But improbable.

When Isaiah T. Montgomery and his associates began acquiring land that would become Mound Bayou, they were not operating in frontier territory. They were operating within the Mississippi Delta — one of the most entrenched plantation economies in the nation.

This distinction matters.

Several all-Black towns were established in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in Oklahoma Territory and parts of Texas and Kansas. Those regions offered frontier conditions: less entrenched plantation hierarchies, lower land barriers, looser political consolidation.

The Delta was different.

It was mature.

It was capitalized.

It was integrated into national cotton markets.

It was politically restructured.

Building an autonomous municipality there required more than optimism.

It required sequencing.

And sequencing begins with substrate.

Mound Bayou did not begin with a hospital.

It did not begin with a bank.

It did not begin with civic rhetoric.

It began with land and rail access.

The land was swampy and wooded. It required clearing and drainage. That reduced acquisition cost and avoided immediate confrontation with established plantation operators who controlled prime cotton acreage.

But undeveloped land alone does not produce leverage.

Transportation does.

The town’s placement along the Louisville, New Orleans and Texas Railroad corridor provided export optionality. Cotton could move outward. Supplies could move inward. Price discovery was not limited to a single intermediary.

Optionality is a form of sovereignty.

Without rail, agricultural communities in the Delta were captive to nearby merchants and plantation-controlled processing facilities. With rail, bargaining position improved — not absolutely, but materially.

Thus, the founding of Mound Bayou was not merely geographic. It was logistical.

It was embedded inside a hostile macro-structure but positioned along an economic artery.

This duality — constraint and connectivity — defines the architectural significance of the town.

It was not insulated from the system.

It was interwoven into it, but on re-calibrated terms.

The question this document examines is not whether Mound Bayou existed.

It did.

The question is how it layered institutions inside one of the most restrictive economic environments in American history — and how long that layering remained coherent under stress.

To answer that, we must begin where it began.

With land.

Foundational Substrate

Land as Leverage in a Plantation Economy

When Mound Bayou was founded in 1887, land ownership in the Mississippi Delta was not merely an economic question. It was a positional one.

In plantation-dominated counties, land determined hierarchy. Those who owned acreage controlled production decisions, labor arrangements, and access to credit. Those who did not own land operated within negotiated dependency.

The postbellum South had transitioned from slavery to sharecropping and tenant farming, but control over land remained concentrated. Many Black farmers cultivated soil they did not own. They negotiated annually renewable contracts. They borrowed supplies at planting season. They settled accounts at harvest.

Land was the axis around which credit revolved.

Without title, collateral was thin. Without collateral, independent credit was scarce. Without credit, land acquisition remained constrained.

This is the cycle Mound Bayou interrupted.

Why Swamp Land Was Strategic

The acreage acquired for Mound Bayou was not prime cotton terrain initially integrated into plantation systems. It required clearing, drainage, and development.

At first glance, that appears disadvantageous.

But undeveloped land carried three advantages:

- Lower acquisition cost

- Reduced confrontation with entrenched plantation owners

- Opportunity for collective development

Purchasing marginal land lowered barriers to entry. It avoided direct competition for already capitalized acreage. It created space for incremental improvement rather than immediate yield maximization.

The cost of development was labor-intensive. Timber had to be cleared. Swamp conditions had to be managed. But labor in this context was not externally hired at plantation rates. It was community-organized.

Development costs were converted into ownership equity.

Ownership changes incentives.

When labor clears land it owns, investment behavior shifts from survival to accumulation.

Rail Access as Economic Oxygen

The presence of the Louisville, New Orleans and Texas Railroad line near the town site altered the risk calculus.

Agricultural production without rail access is captive. Farmers must sell to the nearest intermediary. Intermediaries set prices with limited competition.

Rail connectivity created:

- Access to broader cotton markets

- Competitive pricing leverage

- Supply import flexibility

- Reduced transport friction

The Mississippi Delta was deeply integrated into national cotton markets. Cotton prices fluctuated based on domestic industrial demand and international trade conditions. While Mound Bayou could not control global price shifts, rail access allowed participation in broader pricing networks rather than confinement to local merchant terms.

Optionality did not eliminate volatility.

It reduced captivity.

That distinction is structural.

Acreage and Collateral Formation

Land ownership performs several economic functions simultaneously:

- It produces revenue through cultivation.

- It appreciates over time under favorable conditions.

- It serves as collateral for borrowing.

- It anchors residency and taxation.

For farmers in sharecropping systems, credit was extended against anticipated yield rather than owned assets. That exposed borrowers to price shocks and merchant discretion.

In Mound Bayou, land ownership increased bargaining power with lenders — particularly once internal banking institutions emerged.

Collateral changes negotiation posture.

When a borrower possesses titled acreage, risk allocation shifts.

The lender evaluates asset value rather than only projected harvest yield. The borrower retains agency.

Agency compounds.

Agricultural Revenue Mechanics

Cotton remained the primary crop in the region. Its dominance was not ideological; it was economic. Cotton had established markets, transport channels, and merchant networks.

But cotton revenue is cyclical.

Prices fluctuate due to:

- Global production levels

- Industrial demand

- Currency conditions

- Transportation costs

Communities tied to a single commodity face concentration risk.

Land ownership did not eliminate that risk. It allowed participation in upside pricing while moderating exploitative credit terms.

Revenue, once generated, could be reinvested locally.

Reinvestment is where substrate becomes structure.

Property Continuity and Inter-generational Transfer

One of the least discussed but most significant aspects of land-based autonomy is transfer continuity.

When land is owned:

- It can be inherited.

- It can be subdivided.

- It can be leveraged.

- It can be retained during downturns.

When land is rented:

- Tenure depends on contract renewal.

- Capital improvements benefit the owner more than the cultivator.

- Eviction risk undermines long-term planning.

Mound Bayou’s emphasis on ownership created inter-generational asset pathways.

Inter-generational continuity increases institutional durability.

Without continuity, each generation begins again at baseline.

Tax Base Formation

Municipal governance requires revenue.

Revenue requires taxable property and commercial activity.

Land ownership created a foundation for:

- Property tax assessment

- Infrastructure funding

- Road maintenance

- School support

This connection between substrate and governance is often overlooked.

Without a land base, municipal autonomy becomes symbolic.

With a land base, administrative authority gains operational capacity.

Structural Observation

Mound Bayou did not begin with ideology.

It began with asset positioning inside a constrained economic field.

It selected lower-cost land along a transportation artery. It converted labor into equity. It transformed ownership into collateral. It translated collateral into credit capacity.

Sequence.

Land → Revenue → Collateral → Credit → Structure.

Without land, none of the later institutions could have stabilized.

Substrate precedes architecture.

Commercial Architecture

Processing, Trade, and Internal Circulation

If land was the substrate, commerce was the circulatory system.

Agricultural production alone does not produce durable institutional architecture. Revenue must pass through intermediary nodes before it becomes capital.

In the Mississippi Delta of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, those nodes were typically controlled by plantation-aligned merchants. General stores extended credit, supplied seed and tools, and purchased cotton. Processing facilities — particularly cotton gins — were often positioned to reinforce merchant dependency.

Mound Bayou’s development altered this pattern by internalizing key nodes in the chain.

The General Store as Financial Intermediary

In rural economies, the general store functioned as more than a retail outlet. It operated as a hybrid institution:

- Inventory distributor

- Credit extender

- Harvest purchaser

- Information hub

Under the crop-lien system, merchants extended credit against anticipated harvests. Interest was embedded in pricing. Goods were sold at markup. Cotton at harvest settled accounts.

This arrangement created a feedback loop in which farmers remained tied to specific merchants year after year.

Transaction cost theory suggests that when exchange is limited to a single intermediary, bargaining power compresses and pricing transparency declines.

In Mound Bayou, local merchant ownership altered this dynamic.

When merchants and customers operate within overlapping social networks:

- Credit evaluation incorporates relational knowledge.

- Default risk is moderated by reputation effects.

- Pricing discretion faces community scrutiny.

This did not eliminate profit motive. It moderated extraction intensity.

Extraction is not eliminated by proximity.

It is constrained by cohesion.

Provisioning the Household: The General Store as Daily Infrastructure

Beyond credit mechanics, the general store was the town’s provisioning spine.

Shelves carried:

- Flour, cornmeal, sugar, salt pork

- Dried beans, molasses, rice

- Kerosene for lamps

- Fabric, thread, and work garments

- Farming tools and repair hardware

- Seed for the next planting season

Families did not experience the store as an abstract credit intermediary. They experienced it weekly.

Provisioning rhythms shaped economic behavior.

A farmer who purchased flour and kerosene on credit in February did so with harvest expectations months away. A mother purchasing fabric for children’s clothing calculated durability, not fashion. Every transaction carried seasonal memory.

The store was not merely retail.

It was liquidity extension embedded in daily life.

It was where:

- News circulated

- Prices were discussed

- Harvest forecasts were debated

- Rail shipments were anticipated

In rural economic theory, “search costs” refer to the effort required to find goods or pricing information. In Mound Bayou, search costs were minimal. The store centralized information and goods in one location.

Centralization increases efficiency.

Efficiency increases stability.

And because merchants operated inside the same social networks as their customers, pricing behavior and credit decisions were moderated by reputation effects.

A merchant could charge markup.

But excessive extraction would be remembered.

The general store was therefore not only a commercial node.

It was a reputational marketplace.

Commerce and character overlapped.

Internal Circulation and Capital Velocity

Economic resilience often depends less on total output than on how many times revenue circulates before exiting the system.

This concept — sometimes described as the local multiplier effect — refers to how frequently a dollar is re-spent within a defined geography.

In plantation-dominated areas, revenue often followed this pattern:

Farmer → Merchant → External Bank → Regional Investor

Capital leakage occurred quickly.

In Mound Bayou’s emerging commercial structure, circulation tightened:

Farmer → Local Merchant → Local Services → Local Deposits

The more times revenue transacted internally, the greater the local economic velocity.

Velocity increases employment stability.

Stability increases deposit formation.

Deposits enable credit extension.

Circulation compounds.

Cotton Gins: Control of Processing Layer

Processing is leverage.

Without access to ginning facilities, cotton farmers must rely on external processors who set fees and timing schedules.

Local cotton gins provided:

- Reduced transportation friction

- Processing cost retention

- Timing flexibility during harvest

- Improved price negotiation

Margin on ginning services, though modest per unit, aggregates across volume.

Control over processing compresses dependency.

Vertical integration at even a small scale shifts economic gravity inward.

Lumber Milling and Construction Multipliers

The swamp land that formed the town site required timber clearing. Rather than exporting raw timber immediately, milling capacity allowed lumber to be processed locally.

This created secondary economic layers:

- Construction of homes and storefronts

- Civic building development

- Infrastructure expansion

The multiplier effect here is tangible.

Timber clearing → Milling → Construction → Commercial expansion → Increased tax base

Processing raw material locally multiplies economic impact.

Professional Services and Income Diversification

Commercial density supports specialization.

As storefronts stabilized, Mound Bayou developed a modest professional class:

- Physicians

- Educators

- Clergy

- Business operators

Diversification reduces concentration risk.

A mono-sector agricultural economy is exposed to commodity volatility. Introducing service-based income streams increases resilience.

Diversification does not require scale.

It requires surplus.

Surplus signals institutional health.

Information Networks

Commerce also creates information density.

Merchants observe crop yields, pricing trends, repayment patterns, and consumer demand shifts. In small communities, information travels quickly.

Information asymmetry — a common problem in broader markets — is reduced when actors share social proximity.

Reduced asymmetry lowers transaction uncertainty.

Lower uncertainty encourages credit extension.

Credit extension increases growth capacity.

This loop is fragile but powerful.

Even with internalized commercial nodes, structural constraints remained.

Cotton prices were set in national and global markets. Rail tariffs were influenced by larger carriers. Merchant margins were limited by competition and purchasing power.

Internal circulation increased resilience.

It did not create immunity.

But it bought time.

Time matters in institutional development.

Analytical Observation

Mound Bayou’s commercial architecture demonstrates a subtle but significant shift:

Instead of rejecting existing economic systems, it reconfigured position within them.

It did not withdraw from cotton markets.

It inserted processing and merchant layers internally.

It did not abandon rail networks.

It leveraged them.

It did not eliminate credit.

It re-calibrated its source.

This is not isolationist economics.

It is positional economics.

Financial System Mechanics

Credit, Risk, and Capital Adequacy in a Constrained Economy

Commerce circulates value.

Finance determines whether that circulation compounds or collapses.

In the Mississippi Delta during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the dominant agricultural credit model was the crop-lien system. It functioned as both liquidity mechanism and structural constraint.

Understanding Mound Bayou’s financial architecture requires first understanding the mechanics it was navigating.

The Crop-Lien Model: Illustrative Mechanics

Consider a simplified example.

A farmer requires:

- Seed

- Tools

- Fertilizer

- Household provisions

Assume the total cost of inputs for the season equals $100.

Under the crop-lien system:

- The merchant extends $100 in goods.

- The merchant may embed a 20–30% markup.

- The implicit repayment obligation becomes $120–$130 at harvest.

- Interest is often not separately itemized — it is embedded in pricing.

Now introduce price volatility.

If the cotton harvest yields revenue of $140:

- $130 settles the merchant debt.

- $10 remains as surplus.

If cotton prices decline and harvest revenue equals $115:

- The farmer cannot settle the $130 obligation.

- The remaining $15 rolls forward into next season’s credit.

Debt compounds.

Now add discretion.

The merchant controls future credit extension. If repayment is incomplete, next year’s supplies may carry higher markups or tighter terms.

This system does not require explicit coercion to produce dependency.

Mathematics produces it.

Merchant-Bank Alignment

In many Delta communities, merchants were financed by external banks. The flow looked like this:

External Bank → Merchant Credit Line → Farmer → Cotton Revenue → Merchant → External Bank

External banks captured margin indirectly through merchant financing. The farmer rarely interacted directly with the banking layer.

Capital extraction occurred in stages.

When default rates rose, merchant risk tolerance fell. When commodity prices declined, both farmer and merchant exposure increased.

The system amplified volatility.

Internalizing the Banking Layer

The creation of the Bank of Mound Bayou altered this alignment.

Instead of relying entirely on merchant-financed credit tied to external institutions, deposits within the community could fund loans internally.

Consider a simplified balance sheet scenario.

Assume:

- 200 residents deposit an average of $50 each.

- Total deposits equal $10,000.

If the bank maintains a 20% reserve ratio (a conservative historical assumption), $2,000 remains in reserve and $8,000 becomes lendable capital.

That $8,000 can be allocated across:

- Agricultural loans

- Merchant inventory financing

- Land purchase credit

When loan repayments occur, interest income strengthens capital reserves.

Even modest lending volume changes positional power.

Now, instead of the flow being:

Farmer → Merchant → External Bank

It becomes:

Farmer → Merchant → Local Bank → Local Depositors

Capital velocity increases.

Capital Adequacy and Risk Exposure

Independent banks face structural constraints.

Using our example:

If $8,000 is lent and 10% defaults during a commodity downturn, the bank absorbs $800 in losses.

If capital reserves were initially $2,000, an $800 impairment represents 40% of reserves.

That level of stress threatens solvency.

Small banks therefore operate under tight capital adequacy limits.

This explains why community banks often remain conservative in lending.

Scale provides cushion.

Small institutions rely on repayment discipline and stable deposit bases.

Social cohesion becomes financial infrastructure.

Deposit Stability and Trust Density

Deposits are not static.

If 50 depositors withdraw funds during a downturn — say $2,500 total — liquidity tightens.

If loans are long-term agricultural notes, they cannot be recalled immediately.

This creates liquidity mismatch.

Large banks mitigate this through inter-bank markets and central bank access.

Small rural banks historically had limited inter-bank leverage.

Therefore, deposit confidence is critical.

Trust density reduces bank run probability.

When depositors know borrowers personally, withdrawal panic declines.

Trust lowers volatility transmission.

Risk Pooling Through Fraternal Networks

Parallel to formal banking, the Knights and Daughters of Tabor provided cooperative pooling.

Assume:

- 500 members pay $1 monthly dues.

- Monthly pool equals $500.

- Annual pool equals $6,000.

That pool funds:

- Burial insurance

- Medical support

- Emergency assistance

If 20 members require $100 assistance in a year, total payout equals $2,000, leaving reserve capacity.

This cooperative insurance reduces catastrophic liquidity shocks at the household level.

Without pooling, medical emergencies might force asset liquidation or loan default.

Pooling stabilizes repayment capacity.

Insurance preserves banking health.

Inter-bank Limitations

Independent Black banks in the early twentieth century often faced limited access to correspondent banking networks.

This meant:

- Limited ability to smooth seasonal liquidity gaps

- Reduced access to emergency capital

- Heightened vulnerability to regional downturns

Scale is power in finance.

Mound Bayou’s banking structure operated with constrained scale.

But constrained scale does not mean absent agency.

It means narrower margin for error.

Concentration Risk

Cotton dominance created concentration risk.

If 70–80% of loan exposure is tied to a single commodity cycle, systemic downturns impact the entire loan portfolio simultaneously.

Diversification requires:

- Alternative sectors

- Population density

- Commercial complexity

Mound Bayou’s modest professional class and service layer mitigated but did not eliminate commodity exposure.

Structural Observation

Financial independence in Mound Bayou did not eliminate exposure to:

- Global cotton price shifts

- Regional drought

- National monetary policy

- Technological change

But it changed leverage.

It internalized decision-making authority.

It compressed extraction pathways.

It increased velocity.

It stabilized households through pooling.

Financial architecture layered on land and commerce created compounding effects.

Sequence again:

Land → Revenue → Deposits → Loans → Commerce → Deposits

Circularity builds resilience.

Circularity requires trust.

Healthcare as Labor Preservation Infrastructure

Risk Mitigation, Fixed Costs, and Institutional Dignity

Healthcare in rural economies is often discussed as a moral good.

In institutional terms, it is an economic stabilizer.

By the early twentieth century, access to medical care for Black residents in much of the Deep South was restricted, segregated, or geographically distant. Rural populations frequently traveled long distances for treatment, and facilities available to them were often under-resourced.

Against this backdrop, the establishment of the Taborian Hospital in 1942 represented more than a medical milestone.

It represented vertical expansion of institutional layering.

Fixed Cost Structure of a Rural Hospital

Hospitals operate under high fixed-cost conditions.

Regardless of patient volume, they must maintain:

- Trained medical staff

- Equipment

- Sterilization infrastructure

- Physical plant maintenance

- Utilities

- Administrative oversight

Assume a simplified model:

- Annual operating cost: $100,000

- Staff salaries: $60,000

- Equipment amortization: $15,000

- Utilities and maintenance: $15,000

- Administrative costs: $10,000

If average patient billing generates $50 per case, the hospital must treat 2,000 patients annually to break even.

In rural environments, patient volume can fluctuate.

Volume is stability.

Stability sustains solvency.

Cooperative Financing Integration

The Knights and Daughters of Tabor had already established risk-pooling mechanisms.

Membership dues funded emergency support and burial insurance. Extending that model into healthcare created a prepaid access structure.

Consider a simplified example:

- 1,000 members paying $2 per month

- Monthly pool: $2,000

- Annual pool: $24,000

If a portion of that pool supports hospital operating expenses, the hospital’s fixed-cost burden is partially stabilized independent of per-patient billing.

Pooling reduces revenue volatility.

Volatility is the enemy of fixed-cost institutions.

Labor Continuity

In agricultural and small-town economies, illness directly affects production capacity.

A missed planting season due to untreated infection can alter annual income.

An untreated injury can reduce labor supply permanently.

Healthcare preserves labor continuity.

Preserved labor continuity protects:

- Loan repayment capacity

- Commercial purchasing power

- Deposit stability

- Tax base

Healthcare, therefore, feeds backward into banking and governance layers.

It is not peripheral.

It is central.

A Brief Human Lens

Imagine a cotton farmer in the Delta in the early 1940s who suffers a severe infection after a harvesting injury.

Without local access:

- He travels miles for treatment.

- Delay increases complication risk.

- Work is interrupted during critical seasonal windows.

- Household income declines.

- Loan repayment becomes uncertain.

With a regional hospital accessible within municipal boundaries:

- Treatment occurs earlier.

- Recovery time shortens.

- Productivity resumes.

- Financial stability remains intact.

The difference is not sentimental.

It is structural.

Institutional dignity reduces fragility.

Professional Density and Civic Signaling

Hospitals also attract trained professionals.

Doctors, nurses, and administrators create income diversification.

Service-sector wages are less volatile than commodity-linked agricultural revenue.

Diversification reduces concentration risk in the local economy.

Additionally, the presence of a modern hospital signals institutional seriousness.

Signal effects matter.

Signal strength influences migration decisions, commercial confidence, and long-term residency.

Cost Inflation and Scale Sensitivity

Healthcare costs historically trend upward due to:

- Technological advancement

- Equipment modernization

- Regulatory requirements

- Professional wage increases

Small rural hospitals operate within narrow scale margins.

If patient volume declines from 2,000 to 1,400 annually in our simplified model:

- Revenue falls from $100,000 to $70,000.

- Fixed costs remain near $100,000.

- Annual deficit emerges.

Scale compression threatens solvency quickly.

This dynamic would later matter.

But during its operational peak, Taborian Hospital represented the culmination of layered institutional sequencing:

Land enabled revenue.

Revenue enabled deposits.

Deposits enabled credit.

Credit enabled commerce.

Commerce funded cooperative pooling.

Pooling stabilized healthcare.

Circularity extended upward.

Structural Observation

Healthcare in Mound Bayou was not charity.

It was economic reinforcement.

It stabilized households, protected labor capacity, diversified income, and signaled institutional coherence.

Few rural communities in the Deep South at that time could claim comparable layering.

That fact alone explains why the town became regionally significant.

Municipal Governance Under Constraint

Authority, Tax Base, and Political Paradox

Institutional layering requires coordination.

Coordination requires authority.

From its early years, Mound Bayou operated as an incorporated municipality within the legal framework of Mississippi. It was not an informal settlement. It had a mayor, a council, administrative structure, and local law enforcement.

In the post-Reconstruction South, municipal incorporation was not trivial. It required recognition under state law. It required compliance with state statutes. It required revenue capacity sufficient to maintain public order and infrastructure.

Municipal autonomy existed within constraint.

Constraint defines governance design.

Incorporation as Structural Legitimacy

Incorporation granted:

- Authority to levy local taxes

- Jurisdiction over municipal policing

- Ordinance-making power

- Administrative continuity

Tax revenue — drawn from property and commercial activity — funded:

- Road maintenance

- School support

- Civic administration

Governance without revenue is symbolic.

Revenue without governance is unstable.

Mound Bayou possessed both.

That fact alone differentiates it from informal settlements or loosely organized agricultural clusters.

The Political Paradox: Isaiah T. Montgomery

No serious examination of Mound Bayou’s governance can avoid the role of Isaiah T. Montgomery in Mississippi’s 1890 Constitutional Convention.

Montgomery, a delegate to the convention, supported provisions that would effectively disenfranchise large numbers of Black voters statewide through literacy requirements, poll taxes, and registration barriers.

This decision has generated sustained historical debate.

One interpretation views Montgomery’s position as political accommodation — a pragmatic effort to preserve space for Black institutional development within an increasingly hostile state framework. In this reading, municipal survival required state-level compromise.

Another interpretation argues that supporting disenfranchisement mechanisms, even tactically, reinforced structural inequality beyond Mound Bayou’s boundaries.

The historical record reveals that Montgomery defended his position publicly at the time, arguing that acceptance of certain constraints might secure stability and reduce violence in the long term.

It is important to situate this within context.

By 1890:

- Federal enforcement had withdrawn.

- White supremacist political consolidation was accelerating.

- Violence was not abstract.

- Black political power at the state level was already under systematic erosion.

Montgomery operated within a narrowing decision field.

This does not resolve the moral debate.

It clarifies the constraint.

Governance Within a Restricted Electorate

The 1890 Constitution reshaped the electorate across Mississippi. At the state level, Black political participation declined sharply.

Yet municipal governance in Mound Bayou continued.

Local leadership maintained administrative authority within town boundaries. Ordinances were passed. Taxes were collected. Public services were managed.

Municipal autonomy functioned as a limited but meaningful layer of agency.

Layered autonomy is not absolute autonomy.

It is operational autonomy within higher-level restriction.

Revenue Base and Scale

Let us consider a simplified fiscal model.

Assume:

- 300 taxable properties

- Average assessed value of $500

- Property tax rate of 1%

Annual property tax revenue:

300 × $500 × 1% = $1,500

Add commercial taxes and service fees, perhaps generating an additional $1,000–$2,000 annually.

Total municipal revenue might range from $2,500–$3,500 per year in this simplified scenario.

For a small rural town in the late 19th or early 20th century, such revenue could sustain:

- Basic road grading

- Modest public safety

- Administrative salaries

- School supplementation

Scale remained modest.

But modest scale does not negate structural legitimacy.

Law Enforcement and Internal Order

In much of the Delta, law enforcement frequently reinforced plantation hierarchy.

Local control of policing altered enforcement dynamics within municipal boundaries.

Internal dispute resolution:

- Reduced reliance on external authorities

- Lowered friction between residents

- Reinforced social cohesion

Authority backed by proximity differs from authority backed by distance.

Constraint and Compromise

Municipal governance in Mound Bayou illustrates a broader structural truth:

Institutional resilience sometimes requires navigation within imperfect political systems.

Autonomy may coexist with compromise.

Compromise does not erase agency.

Agency does not erase compromise.

The two can coexist under constraint.

Analytical Observation

Mound Bayou’s governance model demonstrates:

- Incorporation creates administrative durability.

- Tax base enables operational continuity.

- Local authority buffers external volatility.

- Political compromise can coexist with institutional development.

Whether one views Montgomery’s convention role as pragmatism or accommodation, the outcome remains historically significant:

Mound Bayou sustained municipal governance for decades inside a state political structure that restricted broader participation.

That endurance complicates simplistic narratives.

Complexity increases credibility.

Education and Social Cohesion as Economic Multipliers

Literacy, Trust Density, and Institutional Continuity

Institutions do not operate in isolation from culture.

They operate inside norms.

Economic historian Douglass North argued that institutions are the “rules of the game” in a society — both formal rules (laws, contracts) and informal constraints (norms, conventions, codes of conduct). The latter often determine how the former function in practice.

Mound Bayou’s durability cannot be explained by land, commerce, banking, and governance alone.

It requires attention to informal institutional density.

Literacy as Defensive Infrastructure

In the post-1890 Mississippi political environment, literacy was weaponized as a gatekeeping mechanism. Literacy tests and discretionary registration requirements narrowed access to the ballot.

But literacy has dual character.

While it was used procedurally to restrict political participation, it also strengthens economic agency.

A literate farmer can:

- Read loan agreements

- Compare pricing schedules

- Track interest obligations

- Maintain records

- Correspond with suppliers

A literate merchant can:

- Maintain ledgers accurately

- Evaluate risk

- Negotiate with rail carriers

- Interpret market reports

Education, therefore, is not symbolic.

It reduces information asymmetry.

George Akerlof’s later work on information asymmetry would formalize what rural communities understood intuitively: when one party to a transaction possesses superior information, market distortions emerge.

Literacy narrows asymmetry.

Narrowed asymmetry stabilizes markets.

Schools as Institutional Reproduction

Schools in Mound Bayou did more than educate children.

They reproduced institutional knowledge.

Each generation learned:

- Land ownership norms

- Credit discipline

- Civic participation expectations

- Cooperative pooling mechanisms

Institutional memory reduces restart cost.

Without memory, every generation must reconstruct norms from scratch.

Reconstruction increases fragility.

Continuity reduces it.

Social Trust and Transaction Cost Economics

Ronald Coase and later Oliver Williamson developed transaction cost economics to explain why firms and institutions exist. When the cost of negotiating, monitoring, and enforcing agreements in open markets is high, organizations emerge to internalize those costs.

In small, cohesive communities, social proximity lowers transaction costs organically.

When borrowers and lenders attend the same church, shop at the same stores, and share mutual acquaintances:

- Monitoring costs decline.

- Enforcement relies partly on reputation.

- Opportunistic behavior carries social penalty.

Reputation functions as informal collateral.

Informal collateral reduces default probability.

Reduced default probability stabilizes banking.

Banking stabilizes commerce.

Commerce reinforces cohesion.

Circularity again.

The Church as Communication Grid and Civic Square

In Mound Bayou, the church was not merely a spiritual institution.

It functioned as the town’s central communication platform.

Before widespread telephone penetration, before digital networks, before broadcast saturation, information traveled physically and orally.

Sunday service operated as:

- Announcement board

- Employment exchange

- Credit reputation forum

- Political briefing space

- Mutual aid coordination hub

If a merchant extended new credit terms, it would be discussed.

If a family faced medical hardship, assistance would be organized.

If rail shipments were delayed, the news spread by voice.

If elections approached, strategy conversations followed service.

In modern terminology, the church reduced information asymmetry.

It lowered transaction costs by increasing transparency.

It strengthened enforcement through reputational awareness.

It accelerated coordination.

When Douglass North described informal constraints shaping economic outcomes, this is what he meant.

Formal banking contracts may exist on paper.

But enforcement often occurs through social memory.

Reputation formed in pews influenced behavior in storefronts.

The church also created cross-class interaction.

Farmers, merchants, teachers, and civic leaders occupied the same space weekly. That overlap produced cross-cutting ties — a factor political scientists identify as essential to institutional stability.

Without cross-cutting ties, communities fragment into factions.

Fragmentation increases default risk.

It increases political instability.

It increases economic extraction.

The church mitigated fragmentation.

It was the analog social network — not metaphorically, but functionally.

It transmitted information.

It signaled trustworthiness.

It coordinated collective action.

It reinforced shared norms.

If the bank was the circulatory system,

the church was the nervous system.

One moved capital.

The other moved information.

Both were necessary.

Fraternal Orders as Parallel Governance

The Knights and Daughters of Tabor operated beyond ceremonial function.

Fraternal orders provided:

- Insurance pooling

- Burial support

- Dispute mediation

- Organizational leadership training

These organizations created secondary authority structures.

If municipal governance faltered, fraternal networks could coordinate response.

Layered authority increases resilience.

Political scientist Elinor Ostrom’s work on common-pool resource management demonstrated that local communities can design effective governance systems when shared norms and monitoring structures exist.

Mound Bayou’s fraternal networks functioned in similar fashion — not managing forests or fisheries, but managing risk and coordination.

Norm Enforcement and Economic Discipline

In large anonymous markets, enforcement depends heavily on formal legal systems.

In small communities, informal enforcement supplements formal mechanisms.

Failure to repay a loan in a tightly knit town is not merely a financial issue. It is reputational.

Reputational cost influences behavior.

Behavior influences institutional health.

Social cohesion is therefore not sentimental glue.

It is economic infrastructure.

Diversity Within Cohesion

Cohesion does not imply uniformity.

Mound Bayou’s professional class, merchants, farmers, clergy, and civic leaders occupied distinct economic positions.

But overlapping participation in shared institutions — churches, schools, fraternal orders — created cross-cutting ties.

Cross-cutting ties reduce factional fragmentation.

Fragmentation increases institutional decay.

Analytical Observation

Mound Bayou’s layered institutional design depended on:

- Formal rules (incorporation, banking charters, property law)

- Informal constraints (trust, reputation, shared norms)

Douglass North argued that informal constraints often change more slowly than formal rules — and that they can either reinforce or undermine formal institutions.

In Mound Bayou, informal cohesion reinforced formal architecture.

That reinforcement extended institutional longevity beyond what scale alone might have predicted.

Comparative Frame

Why Mound Bayou Was Structurally Different

Mound Bayou was not the only all-Black municipality established in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

In Oklahoma Territory and later the state of Oklahoma, towns such as Boley, Langston, and Taft emerged during a similar period. At one point, Oklahoma contained more than two dozen historically Black towns.

But structural environment matters.

Context determines difficulty.

Frontier Versus Entrenched Plantation Economies

Oklahoma Territory in the late 19th century represented frontier conditions:

- Land was newly opened through federal land runs and allotment policies.

- Plantation systems were not deeply entrenched.

- Political hierarchies were still fluid.

- Agricultural markets were developing rather than mature.

In frontier economies:

- Barriers to entry are lower.

- Capital concentrations are thinner.

- Institutional layering occurs in relatively open space.

The Mississippi Delta was not frontier.

By the 1880s, it was:

- Integrated into global cotton markets.

- Controlled by established landholding elites.

- Embedded in merchant credit systems.

- Politically consolidated through constitutional redesign.

Building an autonomous Black municipality inside the Delta required navigating:

- Existing land concentration

- Merchant-banking alignment

- Crop-lien dependency

- Active political retrenchment

The baseline difficulty was higher.

Land Access Differential

In Oklahoma, land acquisition often occurred through federal allocation mechanisms or purchase within expanding territory.

In Mississippi, land markets were shaped by plantation history and capitalized acreage.

Purchasing undeveloped swamp land near a rail line in Mississippi was not equivalent to acquiring newly opened prairie in Oklahoma.

The strategic decision to select marginal land along transport corridors reflects adaptation to a constrained environment.

Constraint increases cost.

Cost increases risk.

Risk increases institutional significance.

Political Environment Contrast

Oklahoma’s early statehood period involved its own racial tensions and legal segregation policies. However, Mississippi’s 1890 constitutional framework became a model for voter restriction across the South.

Mississippi’s political consolidation preceded Oklahoma’s statehood (1907) and was deeply embedded in post-Reconstruction retrenchment.

Mound Bayou’s incorporation and governance developed inside that already-restricted environment.

It was not building during political fluidity.

It was building after consolidation.

That temporal difference matters.

Economic Integration Level

Oklahoma towns in their formative years operated in developing regional markets.

The Mississippi Delta, by contrast, was deeply tied to established cotton export networks feeding domestic textile mills and international trade.

Participation in a mature commodity market introduces:

- Price volatility exposure

- Merchant intermediation power

- Capital concentration

Mound Bayou’s institutional layering occurred inside an advanced agricultural economy, not a developing one.

The difference is subtle but significant.

Advanced markets offer liquidity — but also concentrated leverage.

Banking and Professional Density

Boley became known for its Black-owned banks and commercial vitality in the early 20th century. These towns demonstrated impressive economic layering under frontier conditions.

Yet Mound Bayou’s development inside the Delta carried additional signaling weight:

- It operated adjacent to entrenched plantation counties.

- It developed healthcare infrastructure in a region marked by segregation and exclusion.

- It sustained governance despite statewide political restriction.

Its resilience must therefore be evaluated relative to environment.

Achievement in open terrain differs from achievement under compression.

Analytical Observation

Comparative analysis clarifies that Mound Bayou was neither anomaly nor miracle.

It was part of a broader municipal movement.

But its environmental constraints were among the most restrictive in the nation.

That increases the institutional significance of its layered design.

Not because it existed.

But because of where it existed.

Structural Stress and Scale Compression

Mechanization, Migration, and Institutional Strain

No institutional architecture exists outside macroeconomic transformation.

For decades, Mound Bayou layered land, commerce, finance, healthcare, governance, and cohesion into a coherent municipal ecosystem. That coherence did not collapse abruptly. It encountered pressure gradually — through technological change, demographic redistribution, and capital consolidation.

Pressure, when sustained, becomes compression.

Mechanization and Labor Displacement

Beginning in the 1940s and accelerating through the 1950s and 1960s, mechanical cotton pickers transformed Delta agriculture.

Where manual harvesting once required dozens of laborers per large acreage tract, mechanized equipment reduced labor demand dramatically.

Let us consider a simplified scenario.

Assume:

- 100 farms averaging 40 acres each.

- Each farm previously required 5 seasonal laborers.

- Total seasonal labor demand: 500 workers.

After mechanization:

- Each farm requires 1 machine operator.

- Total labor demand drops to 100 workers.

That represents an 80% labor contraction.

Labor contraction produces income contraction.

Income contraction produces:

- Reduced commercial purchasing

- Lower deposit formation

- Decreased loan demand

- Tax base compression

Mechanization did not target Mound Bayou.

It altered the agricultural equation across the Delta.

But communities whose economic architecture rested on labor-intensive cotton production experienced disproportionate effects.

Technology does not negotiate with municipal boundaries.

The Great Migration and Population Density

Simultaneously, the Great Migration accelerated.

Between 1910 and 1970, millions of Black Southerners relocated to Northern and Midwestern cities seeking industrial employment and greater political participation.

Population is institutional oxygen.

Let us model the effect.

Assume Mound Bayou’s peak stable population supports:

- 2,000 residents

- 400 taxable households

- 300 consistent bank depositors

- 2,000 annual hospital patient interactions

If population declines by 30%:

- Residents fall to 1,400

- Taxable households fall to 280

- Depositors fall proportionally

- Hospital volume declines

Revenue contraction cascades.

If municipal tax revenue drops from $3,500 annually to $2,400:

- Infrastructure maintenance slows

- Public services tighten

- Administrative flexibility narrows

If bank deposits decline from $10,000 to $7,000 in our simplified earlier model:

- Lending capacity shrinks

- Risk concentration increases

- Capital adequacy tightens

Scale compression is nonlinear.

Small declines in population can produce amplified institutional strain.

Banking Under Concentration Risk

Community banks depend on:

- Stable deposits

- Diversified loan portfolios

- Predictable repayment behavior

Mechanization and migration alter all three.

If agricultural borrowers decline in number but loan exposure remains concentrated in cotton-linked assets, portfolio risk intensifies.

If deposits contract while loan maturities remain fixed, liquidity mismatches increase.

Larger banks mitigate such mismatches through inter-bank markets and diversified geographies.

Small rural banks operate within narrower buffers.

Capital consolidation during the mid-twentieth century further intensified competition. Larger regional institutions gained scale advantages, technological modernization, and regulatory capacity that smaller banks struggled to match.

Scale is insulation.

Smallness requires precision.

Healthcare Fixed Costs Under Volume Decline

Hospitals, as previously modeled, operate under high fixed-cost structures.

If patient volume declines from 2,000 annually to 1,400:

Revenue drops proportionally.

But staffing, equipment, and compliance costs do not decline at the same rate.

If annual operating cost remains near $100,000 while revenue falls to $70,000:

A $30,000 deficit emerges.

Deficits require:

- Subsidization

- External capital

- Service reduction

- Closure

Small rural hospitals across the United States — not only in Mississippi — encountered similar scale compression during the postwar decades.

Taborian Hospital eventually ceased operations in the late twentieth century.

Closure does not erase institutional achievement.

It marks scale insufficiency under transformed conditions.

Capital Consolidation and Market Shift

Postwar America witnessed:

- Expansion of national banking networks

- Growth of suburban commercial centers

- Transportation modernization

- Retail consolidation

Capital increasingly flowed toward metropolitan hubs.

Rural towns across the country — Black and white alike — experienced outmigration and commercial thinning.

Mound Bayou’s structural stress must therefore be situated within national rural contraction patterns.

Its experience was not isolated.

But its layered institutional design delayed fragility.

Delay is not failure.

It is endurance.

Governance Under Fiscal Compression

Municipal governance requires revenue proportional to service obligations.

As tax base contracts:

- Infrastructure degrades

- Public employment narrows

- Investment slows

Autonomy without scale becomes administratively fragile.

Local control cannot reverse demographic decline.

It can only manage its consequences.

Analytical Observation

Mound Bayou’s institutional architecture was not dismantled by singular catastrophe.

It was compressed by:

- Technological displacement

- Demographic redistribution

- Capital scale consolidation

- Healthcare inflation

Each layer — land, commerce, finance, healthcare, governance — depended on population density and circulation volume.

When volume declines, fixed costs loom larger.

Scale compression tests architecture.

Architecture does not fail because it is incoherent.

It fails when environment outgrows its scale assumptions.

Institutional Lessons Under Constraint

Architecture, Scale, and Endurance

Mound Bayou’s historical arc does not argue for replication.

It demonstrates sequence.

Land as substrate.

Commerce as circulation.

Finance as compounding mechanism.

Healthcare as labor preservation.

Governance as coordination.

Education and cohesion as reinforcement.

Douglass North emphasized that institutions persist when formal rules align with informal norms.

Mound Bayou achieved that alignment for decades.

Elinor Ostrom demonstrated that communities can manage shared systems effectively when monitoring and trust are dense.

Mound Bayou’s fraternal and civic networks reflect similar dynamics.

Transaction cost economics explains why proximity reduces enforcement expense.

Mound Bayou internalized that principle.

But scale matters.

Technological shifts can overwhelm labor-based economies.

Migration can thin population below institutional thresholds.

Capital consolidation can outcompete small banking systems.

Healthcare cost inflation can overwhelm rural facilities.

Architecture increases resilience.

It does not guarantee permanence.

That is not a failure of design.

It is a reminder that institutions operate inside time.

Concluding Reflection

Mound Bayou was not mythic.

It was methodical.

Inside one of the most restrictive political environments in American history, it layered institutions carefully and sustained them across generations.

Its existence complicates narratives of inevitability.

Its endurance complicates narratives of fragility.

Its compression clarifies the importance of scale.

What remains is not nostalgia.

It is architecture.

Architecture that demonstrates how land, capital retention, cooperative pooling, governance, and trust can align into institutional coherence.

Coherence is measurable.

Coherence is buildable.

Coherence is vulnerable to scale compression.

But for decades in the Mississippi Delta, coherence existed.

And that fact remains structurally significant.

At InnerKwest.com, we are committed to delivering impactful journalism, deep insights, and fearless social commentary. Your cryptocurrency contributions help us execute with excellence, ensuring we remain independent and continue to amplify voices that matter.

To help sustain our work and editorial independence, we would appreciate your support of any amount of the tokens listed below. Support independent journalism:

BTC: 3NM7AAdxxaJ7jUhZ2nyfgcheWkrquvCzRm

SOL: HxeMhsyDvdv9dqEoBPpFtR46iVfbjrAicBDDjtEvJp7n

ETH: 0x3ab8bdce82439a73ca808a160ef94623275b5c0a

XRP: rLHzPsX6oXkzU2qL12kHCH8G8cnZv1rBJh TAG – 1068637374

SUI – 0xb21b61330caaa90dedc68b866c48abbf5c61b84644c45beea6a424b54f162d0c

and through our Support Page.

InnerKwest maintains a revelatory and redemptive discipline, relentless in advancing parity across every category of the human experience.

© 2026 InnerKwest®. All Rights Reserved | Haki zote zimehifadhiwa | 版权所有. InnerKwest® is a registered trademark of Inputit™ Platforms Inc. Global No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission. Unauthorized use is strictly prohibited. Thank you for standing with us in pursuit of truth and progress!