An InnerKwest Analysis | January 8, 2026

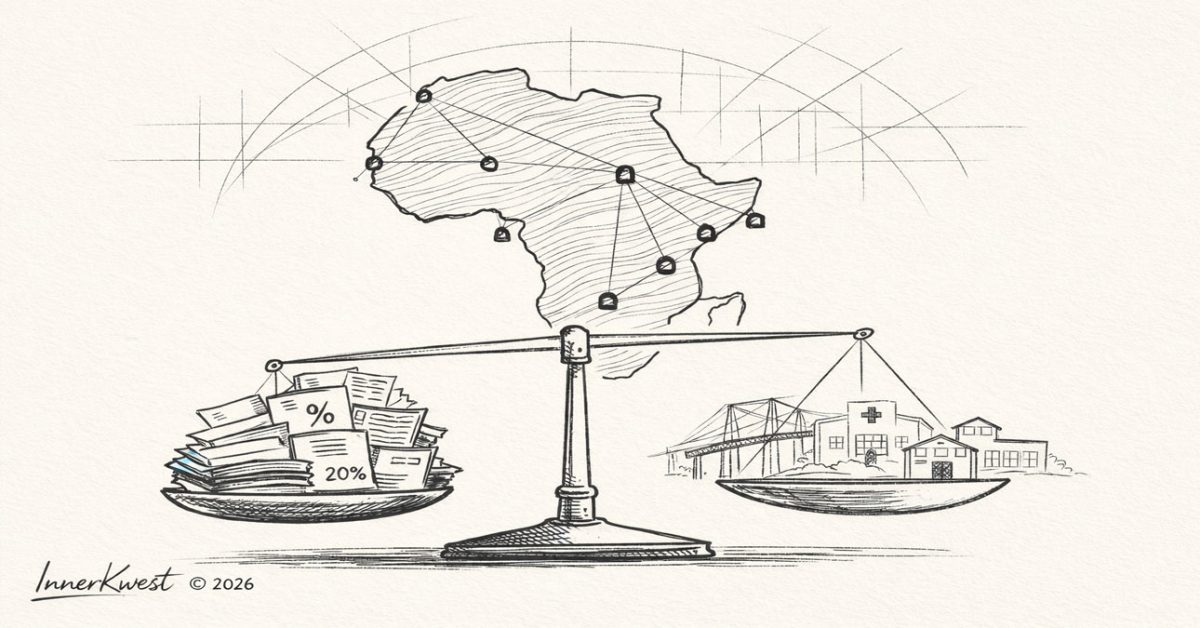

If the petrodollar explained how power was anchored to oil, the modern cost of capital explains how that power is maintained—quietly, technically, and with lasting consequence across Africa.

After the Petrodollar: Where Enforcement Continues

The dominance of the U.S. dollar did not end with oil pricing. It matured.

While the petrodollar system tied global energy trade to dollar settlement, a second layer of enforcement emerged over time—one less visible than currency pegs or military intervention, yet equally decisive. That layer is capital pricing.

Read Related Article: The Petrodollar Order: How Oil Became Currency and Power Became Enforcement

Today, power is exercised not only through who controls commodities, but through who determines the cost of money, the classification of risk, and the rules governing capital movement. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Africa’s position within the global financial system.

The Borrowing Gap No One Explains

African nations consistently face the highest sovereign borrowing costs in the world, even when their macroeconomic fundamentals mirror those of countries elsewhere.

The contrast becomes clearest when comparing Africa with parts of Eastern Europe. Countries such as Serbia, with comparable debt-to-GDP ratios, fiscal balances, and growth trajectories, routinely borrow at a fraction of the interest rates faced by African states.

In many cases, African borrowers pay three to five times more for capital—despite similar data points.

This discrepancy is not explained by balance sheets alone.

It is explained by classification.

Geography as Risk: When a Continent Becomes a Category

In global finance, Africa is not treated as fifty-four countries. It is treated as a single risk condition.

Risk models used by investors, lenders, and multilateral institutions frequently bundle African nations into a generalized high-risk category, regardless of individual governance reforms, fiscal discipline, or growth performance. Political instability, currency volatility, and historical narratives are over-weighted, while diversification, reform trajectories, and regional variation are under-weighted.

Risk, in effect, is priced before fundamentals are examined.

This transforms geography into destiny. Even well-managed economies inherit a premium that has little to do with present performance and much to do with inherited perception.

Basel III: Prudence Codified as Constraint

The most influential force behind this pricing disparity is not ideology, but regulation.

Basel III, developed under the Bank for International Settlements, was introduced after the 2008 financial crisis to make banks safer. Its objectives—higher capital buffers, improved liquidity, reduced leverage—are defensible and widely supported.

But Basel III operates through risk-weighted assets. Every exposure is assigned a weight that determines how much capital a bank must hold against it.

African sovereign debt is assigned significantly higher risk weights than OECD or U.S. sovereign exposure—even when fiscal metrics are comparable. For banks, this makes lending to Africa capital-intensive, balance-sheet inefficient, and unattractive.

Basel III does not prohibit lending to Africa.

It simply makes it uneconomic.

Banks respond rationally:

- interest rates rise

- loan maturities shorten

- capital withdraws during global tightening cycles

What appears as prudence becomes a barrier.

The B20 and the Permanence of “Africa Risk”

Regulatory rules are reinforced by narrative frameworks.

The B20, the official business engagement arm of the G20, plays a central role in shaping how global capital interprets investment environments. Within these discussions, Africa is routinely framed through a risk-first lens—emphasizing volatility, governance challenges, and policy uncertainty.

While these concerns are not unfounded, the framing itself has consequences.

It steers capital toward:

- extractive projects

- short-term returns

- externally controlled ventures

and away from:

- infrastructure

- industrialization

- domestic value creation

Risk becomes self-fulfilling. Capital hesitates, development slows, and hesitation is retroactively justified.

Capital Trapped at Home: South Africa’s Regulation 28

The constraints do not end at Africa’s borders.

In South Africa, Regulation 28 under the Pension Funds Act—overseen by the Financial Sector Conduct Authority—was designed to protect retirement savings through diversification and exposure limits.

Its intent is prudential.

Its effect is directional.

Regulation 28 governs how one of Africa’s largest pools of domestic capital can be deployed. While it safeguards savers, it also restricts pension funds from allocating meaningfully to:

- long-term infrastructure

- industrial projects

- alternative assets critical for transformation

The paradox is stark:

Africa holds domestic savings, yet lacks domestic deployment capacity.

As a result, governments are pushed back toward external borrowing—at precisely the punitive rates imposed by global risk models.

Beneficiation Deferred

High borrowing costs have consequences beyond spreadsheets.

When capital is expensive:

- domestic refining projects stall

- mineral beneficiation is postponed

- industrial supply chains remain externalized

Africa continues to export raw materials and import finished goods—not by accident, but by arithmetic.

Value addition requires long-term, patient capital. The global financial system prices that capital out of reach.

The Debt Trap Without Drama

The cumulative effect is visible in Africa’s debt profile.

African nations collectively owe hundreds of billions of dollars in interest payments to multilateral lenders and external creditors, including the International Monetary Fund and similar entities. Estimates frequently place total interest obligations approaching or exceeding $900 billion over time, depending on rollover cycles and restructuring terms.

Critically, much of this burden is not principal.

It is the cost of servicing capital priced at elevated rates.

With such debt-service pressure:

- infrastructure investment is delayed

- healthcare systems remain underfunded

- education budgets struggle to keep pace with population growth

This is not mismanagement. It is constraint.

Interest payments consume fiscal space, crowd out public investment, and force governments into short-term stabilization at the expense of long-term development.

Nations are asked to stabilize before they are allowed to build the systems that produce stability.

When Stability Becomes the Ceiling

The global financial system is not conspiratorial.

It is structural.

Basel III, B20 frameworks, and domestic prudential regulations were designed to preserve stability. But when stability becomes the overriding objective, transformation is deferred indefinitely.

Africa does not lack discipline.

It does not lack data.

It lacks affordable capital.

And until geography ceases to be treated as a risk category rather than a context, the cost of borrowing will continue to function as one of the quietest—and most effective—constraints on development in the modern era.

The Cost of Normalcy

The most powerful systems do not announce themselves.

They operate through rules that feel technical, neutral, and inevitable.

The price Africa pays is not for excess—but for proximity to a system that prices safety over sovereignty, and continuity over change.

Support InnerKwest: Powering Truth & Excellence with Bitcoin

At InnerKwest.com, we are committed to delivering impactful journalism, deep insights, and fearless social commentary. Your Bitcoin contributions help us execute with excellence, ensuring we remain independent and continue to amplify voices that matter.

Support our mission—send BTC today!

🔗 Bitcoin Address: 3NM7AAdxxaJ7jUhZ2nyfgcheWkrquvCzRm© 2026 InnerKwest®. All Rights Reserved | Haki zote zimehifadhiwa | 版权所有.

InnerKwest® is a registered trademark of Inputit™ Platforms Inc. Global

No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission. Unauthorized use is strictly prohibited.

Thank you for standing with us in pursuit of truth and progress!![]()