Negro Boys Industrial School Fire of 1959 AKA: Wrightsville Fire of 1959

By James C. Frasure III – InnerKwest

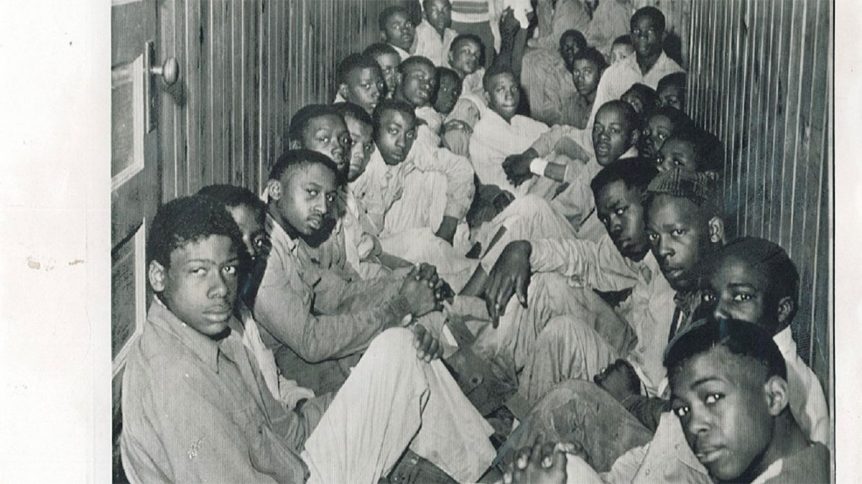

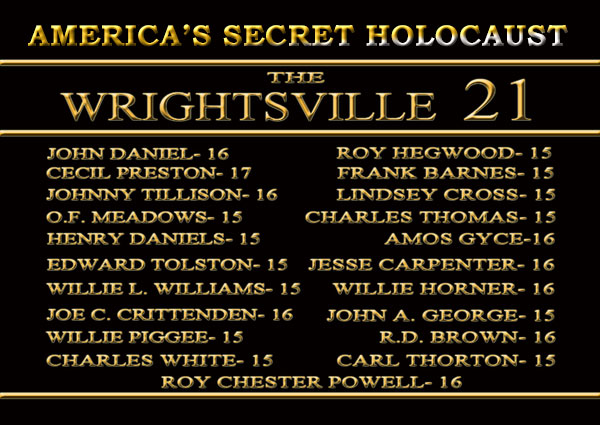

On March 5, 1959, twenty-one African-American boys burned to death inside a dormitory at an Arkansas reform school in Wrightsville (Pulaski County). The doors were locked from the outside. The fire mysteriously ignited around 4:00 a.m. on a cold, wet morning, following earlier thunderstorms in the same area of rural Pulaski County. The institution was one mile down a dirt road from the mostly black town of Wrightsville, then an unincorporated hamlet thirteen miles south of Little Rock (Pulaski County). Forty-eight children, ages thirteen to seventeen, managed to claw their way to safety by knocking out two of the window screens. Amidst the choking, blinding smoke and heat, four or five boys at a time tried to fight their way forward through the narrow openings as the fire began to devour them. Survivors never forgot the horror of that fire. The wife of one of the survivors later said, in an interview before her husband’s death from cancer, that he had continued to dream about the fire.

Fire Kills 21 Young Black

Men In School

The event brought attention to this largely forgotten institution that was operating during the Jim Crow era in Arkansas. Founded in 1923, the Arkansas Negro Boys Industrial School (NBIS) was, for most of its existence, a juvenile work farm located first outside Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) and then, in the mid-1930s, outside of Wrightsville.

The institution became “Exhibit A” for the disparities that prevailed in Arkansas during segregation. Throughout the history of segregation, government employees, historians, and sociologists documented differences in the philosophy and physical structures of the white and black institutions in the state. For example, the 1940 biennial report to the governor notes the following vocational trades taught at a white boys’ school: “carpentry and joining, cabinet work, glazing, painting cement work, brick laying, wood and metal lathe operation, blacksmithing, acetylene welding, plastering, tailoring and shoe mending.” NBIS is mentioned only once—as the recipient of 156 mattresses made by the white boys’ trade school. By the time of the fire, the differences had only marginally narrowed.

A 1956 report by sociologist Gordon Morgan documented the horrific conditions at Wrightsville. It was not merely that “vocational education suffers greatly at the school.” The squalor was mind boggling: “Many boys go for days with only rags for clothes. More than half of them wear neither socks nor underwear during [the winter] of 1955–56….[It is] not uncommon to see youths going for weeks without bathing or changing clothes.” At times, the number of boys at the “school” was over 100. There was no laundry equipment. A single thirty-gallon hot water tank served the bathing needs of the entire population. The water was deemed undrinkable. Employees brought their own drinking water to work.

As an institution for black male delinquents and orphans in an era in which penal conditions were particularly notorious for their routine cruelty and corruption, Wrightsville resembled in some unsettling ways the infamous Arkansas adult prison farm in southeastern Arkansas, popularized in the 1980 movie Brubaker. Wrightsville had all the hallmarks of a junior prison work farm in the making. At the time the decision was made to move NBIS to Wrightsville, the Arkansas General Assembly formally decided that the best treatment for black boys sentenced to the institution was farming. Morgan, the sociologist who had worked on the 1956 report on the school, would later become the first tenured African-American professor at the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County). He wrote in his master’s thesis on NBIS that, in an earlier era, armed guards had overseen the boys in the fields. Boys were whipped with a leather strap for infractions.

The deteriorating condition of the physical plant at Wrightsville may have been a significant cause for the 1959 fire. “All buildings…are in need of extensive repairs, particularly the boys’ living quarters,” Morgan noted in 1956. As Wrightsville was supposed to be as self-sustaining an operation as possible, the emphasis was on farm yields. Maintenance was in short supply or non-existent. Governor Orval Faubus would admit weeks after the fire that faulty wiring may have contributed to the fire.

Although he was noticeably disturbed by the deaths of twenty-one children, the governor acted immediately to guard against their deaths being used as a possible political weapon against him. Even though he had visited NBIS in the past year and had publicly noted its deteriorating condition, he had failed to propose an increase in appropriations to address the issue. In characteristic fashion, the governor went on the attack, insinuating at his press conference the morning of the fire that the blame for the deaths of the boys lay squarely of the shoulders of Lester R. Gaines, the black superintendent. Gaines, he implied, had failed to ensure the safety of the boys by having an employee at the building at night in case of emergency. The reality would be more complicated.

Clearly expecting the board of directors for the school to rubber-stamp his conclusion that Gaines was at fault, Faubus appointed the remaining three members to conduct an immediate hearing to determine where the blame lay. To his obvious chagrin, after interviewing certain employees, his board—whose members he had appointed himself—concluded that Superintendent L. R. Gaines had acted properly and that “everyone had attempted to carry [out] his duty.” The board did nothing more than recommend a “severe reprimand” for the employee who was supposed to be in charge of the supervision that night.

In fact, a careful reading of the admissions and contradictory statements by Gaines given publicly to the press and at the hearing in the days after the fire reveals, at a minimum, negligence and other wrongdoing on the superintendent’s part. At the same time, the Wrightsville institution, through no fault of the superintendent, was dangerously short-staffed, especially in comparison to Pine Bluff. On the night of the fire, the institution for white boys in Pine Bluff had two house parents on duty, and the doors at that institution were not locked at night. The governor told reporters that Wrightsville had a high incidence of escapes, which accounted for the difference in policy. Additionally, Gaines had appeared in person to make the dormitory’s deteriorating condition known to a state legislative sub-committee. Read More

The Wrightsville, Arkansas 1959 holocaust involving the murder of 21 young African American children and the attempted murder of the remaining 48 children will never be forgotten. ![]()

Please consider supporting the advertisers on InnerKwest. Presently we do not place Google Ads on our site. We are setup to do so, but we would prefer to allocate space to our subject matter. The narratives and issues impacting African-Americans and the culture is tantamount to the this platform. Every contribution, however big or small, is valuable to securing our future. Also visit and join the AMIBC Founders Club to maximize the total advantage of being a subscriber. Contribute by clicking on the advertisers featured on AMIBC site and utilize them.

RedaJames Inc All Rights Reserved MMXXI

InnerKwest ™ ® & © 2004 – 2022

Powered By geekPut